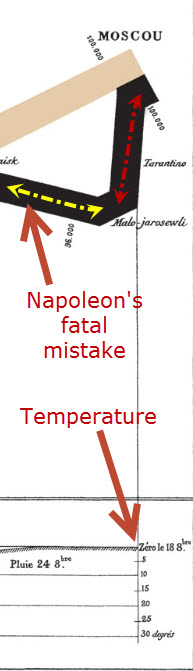

Retreat!

Since Minard’s map is in French, I have provided an English language version for us to use as we discuss the flow of Napoleon’s retreat in detail. [10]

Retreat from Moscow, October 18, 1812 [11]

The French cavalry, commanded by Marshal Joachim Murat, and Marshal Josef Poniatowski’s V Corps were near Tarutino. Some Russian generals, notably Count Levin Bennigsen, wanted to attack them, but Kutuzov realised that his army needed time to rest, recuperate and receive reinforcements.

The rest of the French army was around Moscow. Much of the city was destroyed by a fire that started on 15 September and lasted for three days. City Governor Count Fyodor Rostopchin had made preparations to burn any stores useful to the French and city and had ordered Police Superintendent Voronenko to set fire to not only the stores, but to anything that would burn. Rostopchin had also withdrawn all the fire fighting pumps and their crews from the city.

Zamoyski suggests that the fires started by Voronenko and his men were further spread by local criminals and French soldiers engaged in looting, and by the wind. He contends that the fire left many French troops without shelter. Other historians who believe that the fires were started deliberately by the Russians include David Bell and Charles Esdaile. [2]

David Chandler agrees that Rostopchin ordered the fires, but says that most supplies and enough shelter for the 95,000 French troops remained intact. He argues that a complete destruction of the city would have actually been better for the French, as it would have forced them to retreat earlier. Instead, Napoleon stayed in the hope that he could persuade Tsar Alexander to come to terms. [3]

On the other hand, Leo Tolstoy claims in his novel War and Peace, the most famous book on the 1812 Campaign, that the fire was an inevitable result of an empty and wooden city being occupied by soldiers who were bound to smoke pipes, light camp fires and cook themselves two meals a day. [4]

On 5 October Napoleon sent delegations to attempt to negotiate a temporary armistice with Kutuzov and a permanent peace with Alexander. Kutuzov, who wanted to gain time to strengthen his forces, received the French delegates politely and gave them the impression that Russian soldiers wanted peace.

However, Kutuzov refused to allow the delegation to proceed to St Petersburg to meet the Tsar. He sent their letters on to the Tsar, with a recommendation that Alexander refuse to negotiate, which the Tsar accepted. According to Chandler, Napoleon refused to believe that the Tsar would not negotiate until a second French delegation also failed. [5]

The balance of power was moving against Napoleon as time passed. Chandler says by 4 October Kutuzov had 110,000 men facing 95,000 French at Moscow and another 5,000 at Borodino. The Russians had an even greater advantage on the flanks. [6]

Napoleon had been sure that Alexander would negotiate once Moscow fell and had not planned what to do if the Tsar refused to make peace. According to Zamoyski, Napoleon had studied weather patterns and believed that it would not get really cold until December, but did not realise how quickly the temperature would drop when it changed. [7]

Chandler argues that he had six options:

- He could remain at Moscow. His staff thought that there were sufficient resources to supply his army for another six months. However, he would be a long way from Paris, in a position that was hard to defend and facing an opponent who was growing stronger. His flank forces would have greater supply problems than the troops in Moscow.

- He could withdraw towards the fertile region around Kiev. However, he would have to fight Kutuzov and would move away from the politically most important parts of Russia.

- He could retreat to Smolensk by a south-westerly route, thus avoiding the ravaged countryside that he had advanced through. This would also mean a battle with Kutuzov.

- He could advance on St Petersburg in the hope of winning victory, but it was late in the year, his army was tired and weakened and he lacked good maps of the region.

- He could move north-west to Velikye-Luki, reducing his lines of communication and threatening St Petersburg. This would worsen his supply position.

- He could retreat to Smolensk, and if necessary, Poland the way that he had come. This would be admitting defeat and would mean withdrawing through countryside already ravaged by war.

There were major objections to each option, so Napoleon prevaricated, hoping that Alexander would negotiate. On 18 October Napoleon decided on the third option, a retreat to Smolensk via the southerly route, which would entail a battle with Kutuzov. He ordered that the withdrawal should begin two days later. [8]

Also on 18 October, however, Kutuzov decided to attack Murat’s cavalry at Vinkovo. An unofficial truce had been in operation, so the French were taken by surprise. Murat was able to fight his way out, and Kutuzov did not follow-up his limited success.

However, the Battle of Vinkovo, also known as the Battle of Tarutino, persuaded Napoleon to bring the retreat forward a day. Around 95,000 men and 500 cannon left Moscow after 35 days, accompanied by 15-40,000 wagons loaded with loot, supplies, wounded and sick soldiers and camp followers. [9]

In an attempt to distract Kutuzov, Napoleon sent another offer of an armistice and told his men that he intended to attack the Russian left flank, expecting this false intelligence to reach Kutuzov.

Next: Retreat from Moscow to Smolensk

References

[1] A. Zamoyski, 1812: Napoleon’s Fatal March on Moscow (London: HarperCollins, 2004), p. 333.

[2] D. A. Bell, The First Total War: Napoleon’s Europe and the Birth of Modern Warfare (London: Bloomsbury, 2007), p. 259; C. J. Esdaile, Napoleon’s Wars: An International History, 1803-1815 (London: Allen Lane, 2007), p. 478; Zamoyski, 1812, pp. 300-4.

[3] D. Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1966), pp. 814-15.

[4] L. Tolstoy, War and Peace, trans., A. Maude, Maude, L. (Chicago IL: Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc., 1952). Book 11, p. 513.

[5] Chandler, Campaigns, p. 814.

[6] Ibid., pp. 815-16.

[7] Zamoyski, 1812, p. 351.

[8] Chandler, Campaigns, pp. 817-19.

[9] Ibid., pp. 819-20; Zamoyski, 1812, pp. 367-68.

[10] Mike Stucka, English translation of Minard’s classic chart of Napoleon’s March, Analyticjournalism.com, November 4, 2006, http://www.analyticjournalism.com/2006/11/04/english-translation-of-minards-classic-chart-of-napoleons-march/

[11] Martin Gibson, Napoleon Retreats from Moscow, 18 October 1812, War and Security Blog, October 17, 2012, http://warandsecurity.com/2012/10/17/napoleon-retreats-from-moscow-18-october-1812/.

I used your wonderful translation of the Minard graph in my Medium post. It’s here https://medium.com/@astridafn/the-peace-the-war-and-the-lives-in-between-e1a4fe2178f2#.491ibagog

Thanks so much..