It is 1854 Victorian London and it stinks. Scavengers lived in a world of excrement and death. Unorganized, independent scavengers referred to as bone-pickers, rag-gathers, pure-finders, dredgermen, mud-larks, sewer-hunters, dustmen, night-soil men, bunters, toshers and shoreman spread out in the London nights in search of organic materials to use to make money or for trade.

“Pure” was a polite name for dog shit, the Night-Soil Men clean up the human shit. One account went as follows:

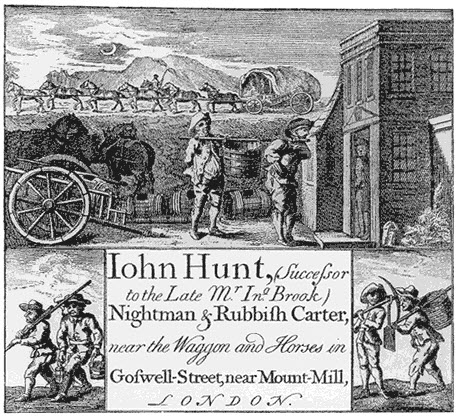

Night-soil men carted human, animal, and household waste in buckets from the back yards of houses, and private and public cesspits, and transported the waste to the country. The men were allowed to work only between midnight and five a.m. They arrived with a cart, and worked in teams of four, consisting of a holeman, ropeman, and two tubmen. The team of men announced their arrival by ringing a bell, which they hand carried. If the privy was located in a narrow back yard, and if the only access the night men had was through the front door, they would have to carry out their work through the house. The men carried their lanters and equipment to the entrance of the cesspit. The holeman would descend first. He would go down a few feet into the pit, loosen the sludge, and shovel it into a tub. A ropeman would then raise the filled tub, and the two tubemen would empty the tubs into a waiting cart. As he emptied the cesspit, the holeman would descend further down the hole. Pulling up the tubs, the ropeman would be careful not to spill too much waste. As the work progressed, the tubmen could easily carry over 100 pounds of sewage. The men would lower a ladder down the increasingly empty cesspit, and the process would be repeated, with the holeman descending the ladder again and again, the ropeman pulling up the waste, and tubmen carrying out the sludge, until the waste was removed. [SOURCE]

London was growing fast. Two and a half million people were crammed inside a thirty-mile circumference. Recycling centers, public-health departments and safe sewage removal had not been invented yet. An underground market was created as the garbage and excrement grew into large piles. Henry Mayhew’s seminal book, London’s Labour and the London Poor outlined the daily routines of these people. The early scavengers of Victorian London weren’t just getting rid of that refuse-they were recycling it.

London was growing fast. Two and a half million people were crammed inside a thirty-mile circumference. Recycling centers, public-health departments and safe sewage removal had not been invented yet. An underground market was created as the garbage and excrement grew into large piles. Henry Mayhew’s seminal book, London’s Labour and the London Poor outlined the daily routines of these people. The early scavengers of Victorian London weren’t just getting rid of that refuse-they were recycling it.

Steven Johnson pointed out that Victorian London had its postcard wonders, to be sure-the Crystal Palace, Trafalgar Square, the new additions to Westminster Palace. But it also had wonders of a different order, no less remarkable; artificial ponds of raw sewage, dung heaps the size of houses.

Trouble was brewing in London. On the 28th of August, 1854, at 40 Broad Street in Soho, Sarah Lewis’ six month old daughter was vomiting and emitting watery, green stools that carried a pungent smell. While waiting for the doctor to arrive, Sarah soaked the soiled cloth diapers in a bucket of tepid water. As the baby girl finally slept, she crept down to the cellar and tossed the fouled water into the cesspool that lay at the front of the house.

The terror was about to begin.

Tomorrow: Henry Whitehead